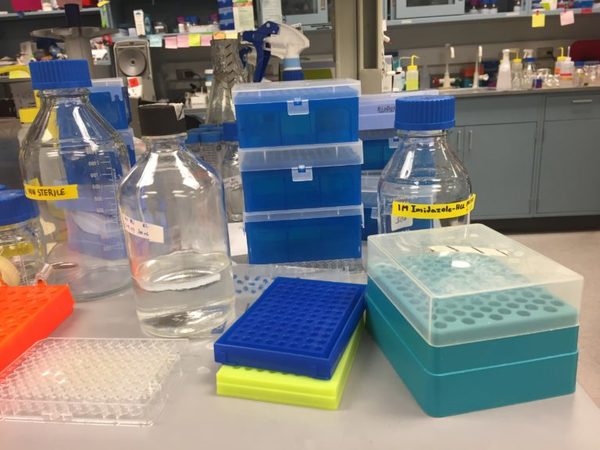

I am a social scientist, embedded in a Molecular Biology lab with a Biohazard Safety Level 2 (BSL 2) rating where I am conducting ethnography and contributing to the efforts of the lab. Sometimes this entails doing PCR amplification, purification and E. coli transformation, and sometimes it means doing mundane work, like filling pipette tip boxes that sit empty on everyone’s bench.

Not even the lab scientists enjoy doing this work; it is a chore not a joy, and this is why empty tip boxes can sit forgotten in a large stack over time. Filling tip boxes does not involve knowing experimental protocols or actual science. It is merely the act of keeping productivity in the lab in a continual flow of progress, however conceived. After all, if tip boxes are empty, then no one can aliquot E. coli, buffer, or other necessary liquids for their experiments. Usually, each person is responsible for filling their own boxes; however, I do this as an act of reciprocation: they have spent valuable time helping me understand their science, so I fill boxes. For me, it is a social effort that helps with the flow of productivity. I was soon to discover that filling tip boxes does have the capacity to transcend the mundane and enter into the domain of morality.

One day in particular, as I filled tip boxes, I had been throwing the tips that had dropped onto the floor into the standard waste basket. This seemed like a normal action, there was nothing chemical or biological on the item; it had simply fallen on the floor. What I was not aware of was the ethical dilemma I had created in that simple, mundane act. When a lab member observed my actions, he stopped his work and explained why the signs in the lab are important and why I should be cautious about where I put the tips.

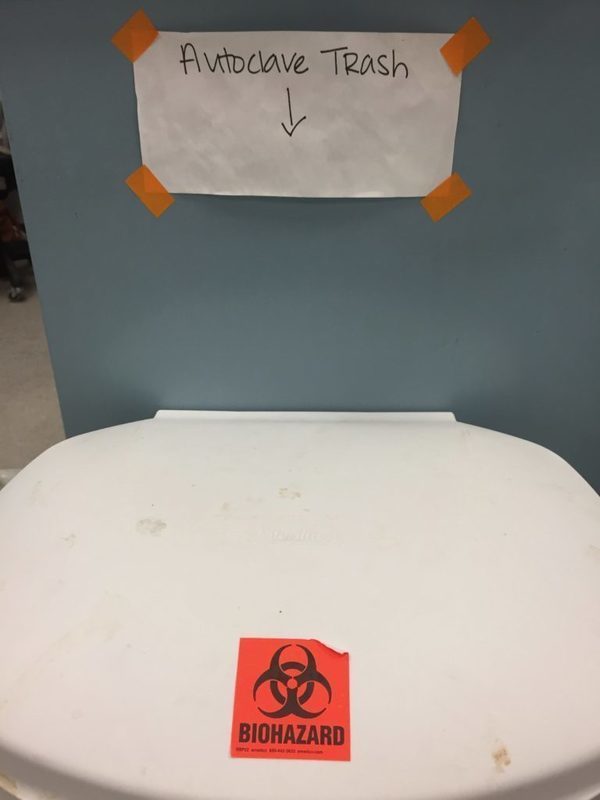

“Here’s the sign,” he said, “that tells you where you should place certain types of waste. You see, the cleaning staff have been trained to avoid contact with lab equipment at all costs, that they most likely contain bacteria that are virulent, therefore able to cause health complications.” So, by putting tips in the regular waste basket, I was contributing to the potential for a kind of slippage in their training. This slippage manifests as they lose the sensitivity to and understanding of the potential hazards of mundane things such as tips. Subsequently, this slippage has the potential to jeopardize their health, as it may be that they actually do touch a tip that contains E. coli. In learning this, my attention was drawn to the numerous signs around the lab in a new light.

Initially, when I first entered the lab, the sign systems were overwhelming and I could not help but wonder how anyone could focus on their bench work with the ‘noise’ of all the signs. My expectations of a sterile, clean, organized environment were dashed quickly upon the sight of these competing signs. The myriad sizes, shape, and colors only add to the chaos that, for an outsider, has become the mark of distinction of some science labs.

What was once something I would describe as visual chaos, had new import. On the front door is a white board that communicates a variety of high priority information; at the computer/work space are signs warning people that Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) is not allowed; each trash container has a sign with information as to what items are to be placed within it, for example: biohazardous (bright orange with the lethal symbol), autoclave trash or just normal, everyday trash. At the PCR bench, there are signs with information regarding PCR gel percentages in relation to the size of the PCR product. Even the color of tape that each scientist uses is a symbol of and a sign for demarcating their items from others. For example, equipment such as pipettes and data stored in the refrigerators.

These lab signs compete for one’s attention regarding the priority and importance of their message. Ultimately these technologies of sign systems, as Michel Foucault[i] suggests, serve as tools indicating a significance for acquiring certain skills and certain attitudes. In this way, Foucault offers a way of thinking about morality that focuses on the character of the individual rather than the rules.[ii] In this instance, the significance of the technologies of sign systems modifies one’s actions and character to not just see the rules readily visible on the signs themselves, but to see the meaning behind the signs in a way that modifies individuals and their skills related to self-care and their attitudes that contribute to the care of others.

Over time, admittedly, order, meaning, and significance have emerged from this chaos of signs. I no longer see them only as clutter and disorder but as important tools for communication and meaning. Moreover, I have experienced the many ways in which this system of signs is operationalized in this environment. This technology of a system of signs, in a Foucauldian[iii] sense, serves not only as a form of communication and influence of meaning between multiple people working in the lab, it also focuses on individual character and the appropriate action to be taken. These sign systems help lab scientists develop meaning that conveys a certain agenda of excellence[iv] in the care of self and others.

Now, as I work in the lab, I ask pointed questions pertaining to the signs I observe to understand more fully their import to each of the lab members. The care of self can sometimes be observed in even the most rudimentary sign, for example, a happy face drawn on a sticky note and left above a lab bench. When I asked about its significance, the character of excellence towards the care of the self and others was made abundantly clear. The meaning of this sign was to modify the lab member’s behavior by reminding him to smile, creating endorphins that support happiness and to spread that smile to others in the lab. As I was reminded, when one person smiles, it is infectious and others will smile in turn. It seems there is more than one variety of contagion in the BSL 2 lab, but thankfully an infectious smile does not have the ethical implications of an infectious tip, and rather, it has the moral implications of impacting human flourishing.

For further reading:

[i] Michel Foucault et al., Technologies of the Self: A seminar with Michel Foucault (University of Massachusetts Press, 1988).

[ii] Richard White, “Foucault on the Care of the Self as an Ethical Project and a Spiritual Goal,” Human Studies 37.4 (2014): 489-504.

[iii] Foucault et al. Technologies of the Self

[iv] Graham Sewell, “Doing what comes naturally? Why we need a practical ethics of teamwork,” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 16.2 (2005): 202-218.

Originally published by at ctshf.nd.edu on June 15, 2017.