This article originally appeared on Princeton Theological Seminary’s Institute for Youth Ministry Blog. As part of the IYM series on science, this article was made possible by Science for Youth Ministry in association with Luther Seminary and the John Templeton Foundation.

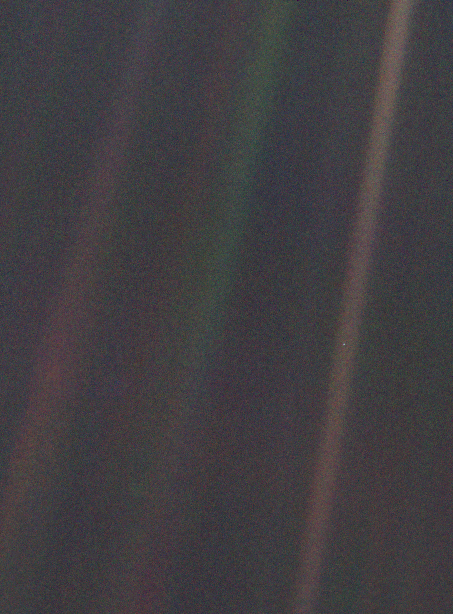

Perhaps you’ve heard of the earth’s most famous selfie. In 1990 the Voyager spacecraft took a photo from more than 3.7 billion miles away, in which the earth appears as a “pale blue dot” barely visible to sight. You may have to squint to see it. If gazing at the night sky does not arouse wonder at the expansive universe, at the earth’s relatively minuscule status, this photo might help.

The scientist Carl Sagan famously and poetically captured the moment, “Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every ‘superstar,’ every ‘supreme leader,’ every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

And here we are, on that suspended mote of dust. This shift in perspective—from our own Tweetable selfies, to that of the earth—gives rise to humility, awe, and wonder. How small we are! How little we know! How relatively brief our existence! Wonder is the natural response.

Terror, too, and perhaps an existential angst. Wonder, awe, and reverence are often tinged with a sense of terror, dread, and fear. The beautifully sublime lightning and thunderstorm draws us onto the porch, but no further. The sublime exposes the limits of our physical and intellectual powers.

Wonder: From Beginning to End

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in Aids to Reflections (1873) wrote, “In wonder all philosophy began; in wonder it ends: and admiration fills up the interspace.” This adage is well known, but the rest of the quote less so. “But the first is the off-spring of ignorance: the last is the parent of adoration” he continues, “The first is the birth-throe of our knowledge: the last is its euthanasy and apotheosis.”

The love of wisdom (philo-sophia), he suggests, begins and ends in wonder. But these kinds of wonder are worlds apart. The first is the progeny of ignorance—the stuff of flying reindeer, tooth fairies, and fairytales. This wonder is a source of curiosity, the inception of all knowledge. The second form of wonder is the culmination and height of philosophy, the result of a life well lived. It’s what remains after we’ve learned all we can learn, discovered all we can know. This wonder births adoration.

We may as well replace the word philosophy with faith. For, faith too has its beginning and end in wonder. All faith begins blind. We trust, we believe before we quite know why—because the Bible tells me so. That’s enough.

The Christian journey is, as Anselm of Canterbury put it, one of faith seeking understanding. We learn, discover, question, doubt, study and square our faith with all that we come to understand about the wide world we inhabit. For some, the journey that begins with faith seeking understanding includes periods of understanding seeking faith. Faith born of wandering in the wilderness is no less full of wonder, but it’s a sense of wonder and gratitude that rises out of the ashes.

A Fork in the Road?

This is one way of describing Mike McHargue’s journey as told in his book, Finding God in the Waves. His story is all too familiar to those who find the faith of their youth or church on a collision course with their broadening understanding of the world, scientific or otherwise. For Mike, it was science.

The evangelical church of his youth could not accommodate his scientific understanding of the world—a world that is 4.5 billion years old, in a milky-way galaxy three times as old.

He came to a fork in the road. Signposts read “God” or “Science.” Convinced that he had to choose between faith and science, church and truth, Mike lived as a closet atheist for years before “coming out.” Unfortunately, his church was not a safe place for someone with faith in God to seek scientific understanding. Eventually, he left. His journey became one of scientific understanding seeking faith.

His story does not end there. On the back end of a weekend at NASA he has a set of mystical experiences, which ultimately yield a new sense of awe and wonder, a new ability to reconcile scientific understanding and faith in the mystery of God.

Yet science is not the only obstacle to his faith. A subtext of the book, is the question of evil. How do we reconcile faith in a good and loving God with the reality of evil?

In a video that echoes the conclusion of the book, he says, “when I see protesters under impossible assault still stand on a street and say Black Lives Matter… I find a beauty and a mystery, and only one word will do to articulate it, and that word is God.” Science cannot capture this spiritual insight. “When I realize each breath is something I just get for free,” he continues, “I am compelled to gratitude.” Christians have another word for this free gift, namely grace. Amazing grace.

A Fork-less Road

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s journey did not lead him to atheism and back again. He simply didn’t experience a fork in the road, a choice between faith in God and science. His address to future ministers in 1838 begins where Mike ends: “In this refulgent summer, it has been a luxury to draw the breath of life.” This sacramental opening line is the theological heart of the address. It’s a reflection of one on a journey of spiritual ascent—like Moses and Elijah to the mountain, like Peter, James, and John with Jesus.

The height of this faith journey, this pilgrimage of ascent, is what Emerson calls the “religious sentiment.” This sentiment “makes the sky and the hills sublime, and the silent song of the stars is it.” By this sentiment or faith perspective, and not by “science or power,” he tells the new ministers, “the universe is made safe and habitable.”

How does this faith make such a perilous universe safe, if not through withdrawal, domination, or control?

It does not immunize us from dangers, toils, and snares. Rather, it empowers us to live well, even die well, in their midst. It enables one to make a home of the world—not because the world is as it ought to be, but because she is as she ought to be in it. Through love and justice, Jesus made a home of first century Palestine under Roman imperial rule, Dietrich Bonhoeffer of Nazi Germany, and Martin Luther King Jr. fighting for civil rights under the oppressive regime of Jim Crow.

The religious sentiment is a faith full of both understanding and wonder. For Emerson, this faith is compatible with the best science of the time. He was enamored with nineteenth-century science. He kept up on the latest developments in chemistry, physics, electro-magnetism, optics, and evolutionary theory. He thought, “as large a demand is made on our faith by nature, as by miracles.” Life itself is a miracle, a luxury, a gift.

Emerson’s journey is quintessentially one of faith seeking understanding—even scientific understanding. This understanding led to a deeper faith, a new sense of awe and wonder.

Wandering and Wondering

What lessons can churches today glean from “Science Mike” and Emerson?

If the Christian journey of faith seeking understanding is one that begins and ends in wonder, then the church needs to be a safe place to ask big questions about God and about God’s expansive universe. It needs to be a safe place to question and doubt, to read and study, to learn, grow, and mature in faith. Better yet, the church should be leading the quest for understanding. It should be the vanguard! We have nothing to lose, least of all our faith.

If the Christian journey of faith seeking understanding is one that begins and ends in wonder, then the church needs to be a safe place to ask big questions about God and about God’s expansive universe.

The faith and wonder of youth is a wonderful place to begin, but a lousy place to remain. The church is tasked with helping young adults to grow in faith, wisdom, and understanding. The mature fruits of this labor will be renewed wonder. As Coleridge suggests, the first wonder leads us to seek understanding, the last reminds us of its limits.

This shift in scope—from the reach of our own selfie stick to that of the Voyager—need not leave us paralyzed with fear, nor faithless. For those with eyes to see, ears to hear, the sublime and beautiful meet us, in the mundane as at the far reaches of our galaxy. They meet us in protesters chanting “Black Lives Matter,” in those who lay down their lives for friends and enemies alike, and in the grateful recognition of the luxury to draw the breath of life. May we be a people of faith seeking understanding as we live out our days on this pale blue dot. May the greatest scientists of our time still join the chorus:

I wonder as I wander out under the sky

How Jesus the Saviour did come for to die

For poor on’ry people like you and like I;

I wonder as I wander out under the sky

Originally published by at ctshf.nd.edu on February 23, 2017.