Her arm moves fluidly through the air, up and down—back and forth, almost rhythmically to a timing that is not discernible by anyone other than herself. As an observer of this activity, I notice a certain aesthetic to this behavior; it appears to be tolerantly accepted in spite of the mundane repetition.

It is flawless, embodied, and intentional at the same time. Occasionally she looks down at the platform below her, referencing a stack of papers or notes that seem to dictate her next moves. In some instances, she makes a note on her stack of papers and then goes back to the activity, as if there was never a break in this fluidity. Only this time, she has incorporated some slight adjustment based on her notes, adjustments that, when operationalized, are invisible to the common observer.

In total, this is a set of moves that has undoubtedly taken a length of time to practice and perfect, but which practice does this behavior represent?

Working on the ethnographic aspect of the Developing Virtues in Scientific Practice project, I have observed this kind of behavior in both the science labs and the choral ensemble that constitute our multi-sited study. With respect to the field site, this description is written in a vague manner in order to highlight that from observation alone, these two practices may appear homogeneous. However, participation coupled with observation can suggest otherwise.

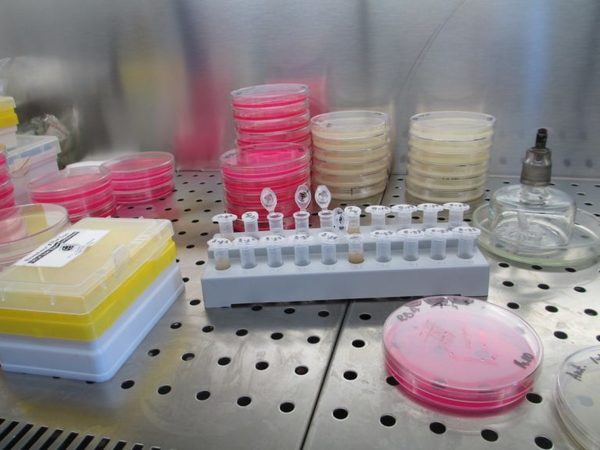

This description represents aspects of laboratory science, specifically working under the hood where pipettes are filled with medium and added to beakers for an experiment that answers a question addressing the overall research objective of the lab. As this activity occurs, the bench scientist may identify an action or measurement that needs adjusting in the protocol she is following. This description also represents the movements of the director of a choral ensemble, where she is working through a new piece of sheet music with the choral singers during rehearsal. As she hears the singers respond to her direction, she may make notes in the sheet music about where to pause for a breath, or how words might be pronounced in order to perfect articulation through song.

In each of these practices, the repetition and perfection of these actions serve a purpose, a particular end. These actions are purposeful in the repetition, they become embodied by the individual in order to perfect the action, and this then lends to the purpose of what kind of scientist or choral director these individuals want to be. The juxtaposition of these behaviors with the ends ultimately drive the interest of this ethnographic study of virtues in scientific practice, where the choral ensemble constitutes one comparative component of this work. In taking a virtue perspective, what can this tell us about the practice and the character of its practitioners? Generally speaking, in taking this approach, the analytic objective lends itself to understanding how, as agents, we should live and what kind of person we want to be.1

Applying this analytic for the purposes of this post, specifically to the scientific component of this study, a virtue perspective informs us of the ways scientists feel they should live as scientists and what kind of scientists they want to be. This is possible through ethnographic inquiry as “virtue expresses the qualities needed to excel in the practice viewed from the inside.”2 Being inside the lab, both observing and participating, is pivotal to understanding this particular view of laboratory science.

A View from the Inside

How can these observations unpack the qualities needed to excel in science? Generally speaking, in the everyday practice of laboratory practice, data are the key to any publication. However, not just any data, the right kind of data; they must lack any ambiguities and be easy to interpret. In other words, the data are characterized as having a clarity that is indisputable. This is supported by what is often heard in lab meetings, “I can’t quite make out that slide. How sure are you of [these] data? Have you replicated this result? How many times have you replicated it” Considering this, the actions that result in the right kind of data are an important aspect of individual motivations for how these data are constructed and produced from the start, or in some cases when it is necessary to replicate data. As data are key to getting published, in the everyday life of lab scientists, this circles back to an end, that is the kind of scientist who is able to produce the right kind of data, qualified as indisputable in its interpretation and able to be replicated.

Learning how to conduct experiments—Western blots or BACTH transformations—as a graduate student and member of a lab, is just one step in being recognized by peers as the kind of scientist capable of producing the right kind of data. For example, when the Principle Investigator (PI) requested two specific lab members to work together and “be meticulous in their work to create new stock,” this suggests that these individuals are recognized as capable of producing the right kind of data. Meticulous is not a word that is imposed on this analysis; however, it is used daily in conversations between the PI and lab members. Meticulousness in this context involves care, attention to detail, and precision. How a lab member negotiates this everyday environment is inextricably linked as a means to an end of how one should live and what kind of scientist one aspires to be in this environment.

In light of this, there is a temporal aspect in this right kind of data as an outcome of a meticulous experiment, not just the first time but several times. The level of care, attention to detail, and precision required over a length of time to be qualified as a meticulous scientist involves virtues such as patience and perseverance. These are not virtues exclusive to scientific practice; however, in this specific scenario, they are fundamental to it. Reflecting back on the description that began this post, where the scientist is working under the hood, patience is an important virtue. This patience is qualified as a totality of fluid actions, observations of method, making corrections and starting again by operationalizing the corrections—not just once, but several times over the course of an experiment and waiting for the results to suggest success. This also suggests endurance, such that repeating this process results in these movements and correctional observations being embodied. This endurance is not blind; it is for the very purpose of reaching a goal—the right kind of data despite the repetitions or trouble shooting involved.

Perseverance in the face of difficult experiments and patience in reproducing the necessary steps for the right kind of data are necessary virtues in laboratory science. They are also qualities, as seen from the inside of laboratory science, that are necessary in becoming a meticulous scientist. It is too early in the fieldwork we are conducting to speculate if these are virtues that are fundamental to the aims of science overall; this is something that we anticipate will emerge as we continue working inside laboratory science. Watch this space.

1 Lambek, Michael, Value and Virtue (Anthropological Theory, 2008, Volume 8, Issue 2, pages 133-157).

2 ibid, page 151.

Originally published by at ctshf.nd.edu on November 03, 2016.